Our first workshop takes place 28-30 August 2019 at the University of Munich and we will be discussing the following papers.

To read the full abstracts, click on the arrow the expand the text.

Back to the Roots

Voices on “Asia” and “Europe” from Ancient Greek Drama.

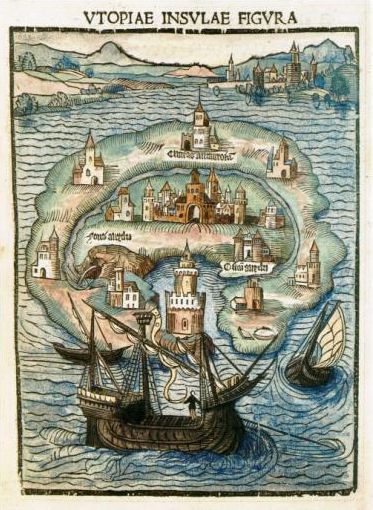

The publication of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia in 1516 holds up a mirror to European governments through the fictional imaginings of the political, religious, social and economic life of a fictional island. This paper will look at the views held in Utopia then and will examine the ways in which it continues to inspire political thought in modern Europe.

Looking at Europe from Outside

Imagining Europe at the Early Modern Mughal Court.

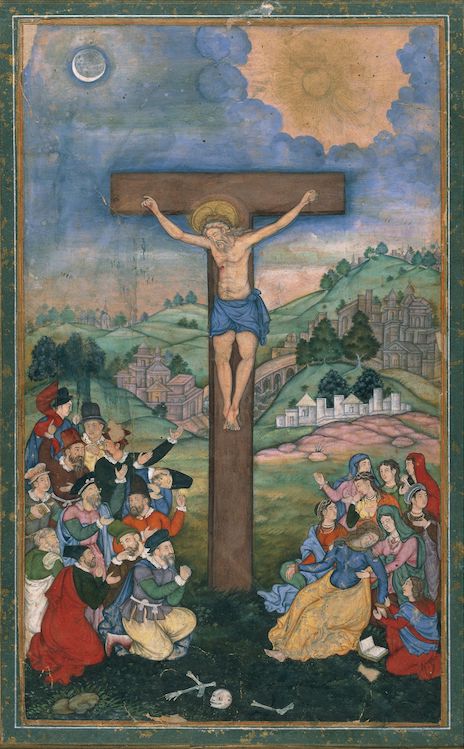

The court of the Mughal Padishas, who after conquering Delhi in 1526 became the most powerful dynasty on the Indian subcontinent, was a religious and cultural melting pot. In the last quarter of the 16th century the Mughals intensified their contacts with Europe inviting diplomats as well as missionaries to their court. The paper asks for the concepts and ideas of Europe that the European visitors communicated at the Indian court and the understanding of Europe and the “farangi” (literally “Franks“ i.e. “Europeans”) the Mughal sovereigns and courtiers developed through this contact. One of the most important aspects in these definitions of a European identity was the Christian faith. The paper will lay a focus on the role of art and visual representations in shaping the image of Christian Europe. Did the missionaries and diplomats introduce a normative concept of Europe? How did the Mughals react to the presentation of a Christian-European identity? What implications had the Christian religion for these images of Europe?

Borders in Europe

A Shattered Whole? Imagining Europe in Pieces.

Academic scholars agree that “the story of the interrelationships between Mormonism and American culture is reasonably clear (Jan Shipps 58).” The religion has been founded in 1830 in upstate New York. Soon after, namely in 1837, the first European mission opened in England and in 1840 the first mainland mission in Germany (‘LDS Statistics and Church Facts | Total Church Membership’, www.mormonnewsroom.org.) Today more than half a million Mormons live in Europe. But how did this religious community adapt to Europe and what is left of their American heritage?

Until today the challenge for the LDS Church in Europe is not only to acquire new converts but also to adapt their worldview that is tailored for the United States to an European standard. The question what an US American compared to an European standard means in the context of this adaptation process is at the core of the contribution. From a contemporary perspective the contribution looks at teaching documents, mission statements, video- and audio sources, and other church materials used in Europe to analyse how the LDS church communicates their messages to their European members and possible converts.

Economical Representations

Immaterial Materiality: Money as “Absolute Aean” and the Temples of Monetary Authority.Performing Representations

Arab Media Representations of Drone Technology and Europe’s Visible and Invisible Connections to the Global War on Terror.

Ever since the pictorial turn (Mitchell 1994), it has been widely acknowledged that major political and social events are interlinked with visual culture. The terror attacks of 9/11 are a case in point. However, in this project I’m interested in a diametrically opposed, but related phenomenon, namely the increasing usage of drone operations and “targeted killings” in warfare, especially in the so called global war on terror, and their almost invisibility in (mass) media representations.

European countries provide technological assistance to the American war on terror, for example with the satellite relay station at the Air Base Ramstein (Germany, headquarters for the US air forces in Europe). Without it, the drone warfare would technically not be possible. Consequentially, victims of drone attacks hold European countries responsible for their harm and losses (Starski 2015).

I will explore Arab media representations (Satellite-TV talkshows, newspaper article, text-, video- and audio material) regarding the drone killings in Yemen since the year 2002 (when the first person was killed this way) in connection to it’s relationship to Europe.

Hence, I will deal with the image of Europe and Europe as an imagined ally in the war on terror and against it. Arab media representations of Europe in connection to the global war on terror are especially interesting because they address Arab speaking populations (in the Arab regions and elsewhere) that are not only spectators but are also supposed to be victims of those drone killings.

- How does the book constitute an idea of Europe? What kind of elements partake in the representation of Europe?

- To what extent are religions relevant to the generation of Europe? Are religions represented as connecting or separating phenomena in an equal or diverse imagination of Europe?

- How does the anthology frame concepts of culture, folklore, religion and custom? How are the terms connected to each other?

- To what extent are country-specific and common European identities imagined? What kind of “identity-markers” are presented (e.g. nationality, religion, history)?

The project focuses on representations of religious symbols, communities and customs in the construction of European identities. The theoretical approach embeds religions as systems of symbols in cultural surroundings. Supposing religion to be a system of communication, the interaction of representation, production, consumption, regulation and identity becomes important regarding medial transmitted and transformed interdependencies. The analysis focuses particularly on representation and identity and aims to reconstruct normative ideas of a European unity.

The Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) is a music competition held among the members of the European Broadcasting Union. This show was created in 1956 and has regularly been broadcasted to European televisions since its inception. In the ESC Europe is on the one hand constructed as unity of different and diverse countries contesting each other; on the other hand Europe is staged as a supranational, perhaps “common” popular culture. References to religious traditions play various roles in this competition: For example since 2002, the show is framed by different slogans that contain religious references and point to an exceptional or even supernatural sphere. Such slogans include “A Modern Fairytale” (2002); “Magical Rendezvous” (2003) or “Dare to Dream” (2019). Also different artists have included religious motifs in their performances (lyrics or the show on stage) since the beginning of the ESC. I want to analyse in my paper one particular example of such a performance that links entertainment, a promise of an extraordinary experience and explicit references to religious motifs: the Finnish Hardrock-Band Lordi who won the Eurovision Song Contest in 2006 with their hit “Hard Rock Hallelujah”.

My contribution, in line with my usual methodology as a visual reception historian, will explore one strand of the complex reception history of Genesis 11.1-9 (The Tower of Babel Narrative). In 1563, Niclaes Jonghelinck commissioned Breugel to paint (among other subject matters) a painting of the Tower of Babel for his private collection, which was bequeathed to the city of Antwerp shortly thereafter. The painting can be viewed on two levels, as both an ambiguous evocation of the biblical Tower of Babel prior to its collapse and as a reminder to the rulers of the rapidly growing international metropolis of Antwerp of the need for good communication and a common purpose. Within this second ‘reading’ Antwerp can be read as a symbol of Europe as a whole, which was also undergoing rapid development at this time. Although The Tower of Babel has been visualised by many other artists (see Lucas van Valkenborch and Gustav Doré to name but two well-known examples) it is the Breugel image that has had the furthest reach, not least because it was used as the inspiration for the EU Parliament Construction poster of 1992 and because the building itself bears a striking resemblance to Breugel’s unfinished tower. Although the poster was later withdrawn after complaints from Christian groups, the image had entered the popular imagination, in both positive and negative ways. For supporters of the European project, the EU Parliament building and the ‘Many Tongues, One Voice’ Poster of 1992 are a symbolic representation of the whole enterprise, which might be seen as an (albeit secular) attempt to ‘reverse Babel’ and demonstrate the positive effects inter-European collaboration and dialogue. At the other end of the spectrum, for a whole array of ‘end times’ Christian groups, bloggers and polemicists, the appropriation of both Breugel’s image and by implication the Genesis Babel narrative by the EU, is yet further evidence that the EU is a representation of the Beast of Revelation 13 and the Antichrist. Thus this contribution will explore the normativity of the Babel image as a symbol of Europe (as primarily expressed in the Breugel image) within two very different world-views.”

Our contribution focuses on the role of the museum as a specific place in society. In a dialogue between philosophy and the study of religion we are dealing at the House for European History in Brussel, a museum initiated by the President of the European Parliament in 2007 and inaugurated in 2017. In our analysis, three aspects of the museum are highlighted: First, the museum as a place of bodily performance, were visitors are reconstructing pieces of European history by means of walking through the building; second, the material objects displayed in the museum and their references to religious historical aspects; third the concepts of memory and European identity suggested by the permanent exhibition. The analysis of the museum aims at deepening the representation (or negation) of religious diversity, the concepts of plurality and the values linked to the suggested construction of a common past and future for Europe.

There is, in today’s multicultural and multimedia society, an intense preoccupation with foods and health, with different approaches to nutrition, multiple ways of preparation and increasingly complex discourses of (in)tolerance. Museums dedicate elaborate exhibitions to different aspects of food and drink cultures, research is published that praises the virtues of some foods and condemns the negative effects of others. Highly frequented blogs, sophisticatedly designed cookbooks, popular television shows and documentaries discuss food as cultural heritage as well as the latest gastronomic and dietary trends.

Focusing on “Europe” as a frame of reference that was and remains highly complex and contested, we suggest approaching this broad topic as an open experimental space within visual and material communication and culture. This may allow including empirical dimensions as much as theoretical and methodological considerations, and the use of heuristic tools and epistemologies from different disciplines on religion, food, identity and normativity. Possible questions could deal with historical and present-day representation of food, with the media discourse on nutritional beliefs and the norms regulating them, with congruencies between a dietary self-optimization with super foods and a spiritual search, with individual and collective ways of orientation and identification offered by preparation methods and ingredients.

The speech addresses the role of Christianity in Europe and begins with the following question: «What is our responsibility at a time when the face of Europe is increasingly distinguished by a plurality of cultures and religions, while for many people Christianity is regarded as a thing of the past, both alien and irrelevant?» According to Francis, the two main contributions that Christians can give to Europe is to recall to memory, first, that Europe is not only an Institution but also made up of people and, second, that personal identity is primarily relational and thus can be realized only within a community. Person and community are (or should be) the foundations of Europe. Pope Francis continues by exposing what he calls «integral conception of man» (an evident reference to Jacques Maritain’s «Integral Humanism»), arguing for a inclusive European community capable of assuming moral responsibility «especially when faced with the tragedy of displaced persons and refugees.» Finally, the Pope concludes arguing that Christians have «to be the soul of Europe» and «to revitalize Europe and to revive its conscience, not by occupying spaces – this would be proselytizing – but by generating processes capable of awakening new energies in society.»

Starting from this speech, the paper aims to highlight and critically inquire into the Pope’s strategy of intervention within political discourses and debates about the future, problems, tasks and objectives of the European Union. The main questions are: what image, what vision of Europe is presented by the pope in his speeches? What figures of speech and narrative/communicative strategies does he use to present his idea of Europe? How do the mass media and political representatives react to his speeches?